A commonly accepted approach to decarbonizing our energy mix is to increase the use of electricity in transportation, heating, and cooking. In order to achieve this, it is also commonly accepted that we need more electricity from clean energy and have it transported to where it will be consumed.

However, in order for a supplier of clean electricity to connect to the grid, permits are needed. Before a transmission tower to transport that electricity can be built, permits are needed. Currently, the processes associated with getting those permits takes years. A 2020 report by the White House Council on Environmental Quality found the average time to go from Notice of Intent to Record of Decision across all federal agencies was 4.5 years. In addition, according to the federal government website permits.performance.gov, permits can involve up to over 60 different governing bodies. And that is just at the federal level. There are also state, county, and municipal authorities involved. This situation is too long and onerous relative to magnitude of the need and the urgency in getting things done in order to address our climate problems. This is why there is pressure to reform the permitting processes.

Adding to that pressure, the Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory, a Department of Energy laboratory, says 676 GW of solar capacity and 247 GW of wind capacity is waiting to be connected to the grid. To put those numbers in perspective, the Energy Information Agency says the US currently has a total capacity of over 1140 GW with 311 GW or 27% coming from clean energy. So, an additional 923 GW of clean energy is waiting to be added to our 1140 GW of capacity or replace existing dirty electricity capacity.

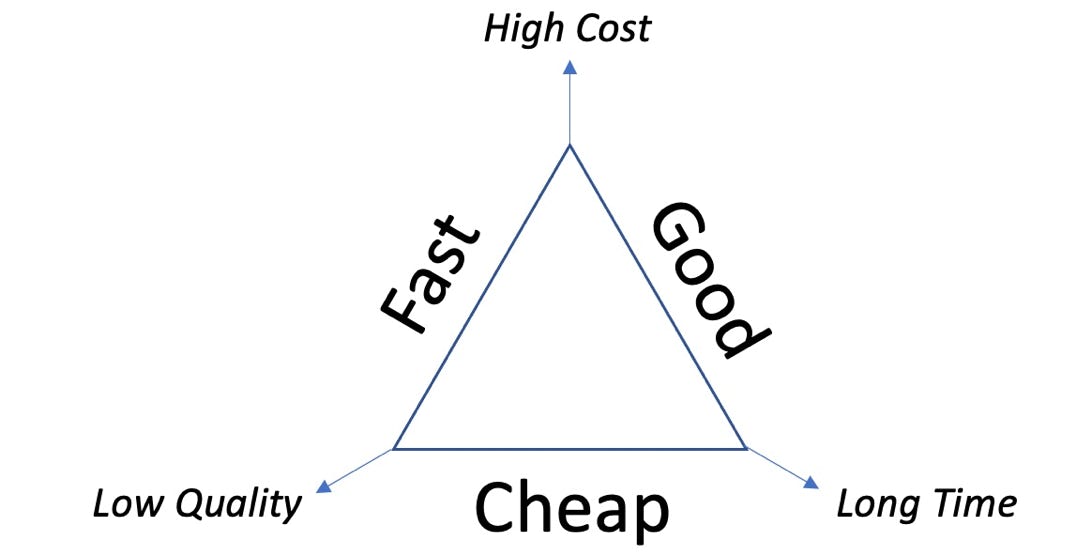

In reforming the processes to get this capacity online, it is important to understand something called the Tradeoff Triangle. The Tradeoff Triangle says there are three qualities associated with the execution of a process - cost, speed, and quality. However, you can only have two of the three while giving up the third. For example, if you want a process executed cheaply and quickly, it will be done low quality. If you want the process done well and quickly, it will be expensive. The figure below depicts the Tradeoff Triangle and the various scenarios.

If you buy into the Tradeoff Triangle, it presents a challenging questions for the process reformers. How can the proper risk-reward balance be achieved when there is urgency in getting the clean energy generated and distributed? How much are we collectively willing to pay to have it done faster? How much are we willing to give up in comprehensiveness in order to have it done faster? Who defines what is an acceptable level of environmental justice? Permit reform only gets more complex when you take into account the many stakeholders involved.

From the seat I sit in, the approach to permit reform starts with governance. The 60+ groups noted earlier are largely if not totally independent of one another. Reforming the permitting process at the federal level must begin with establishing some kind of oversight organization that can manage all permit applications through every relevant governing bodies. Let me call it the Permit Management Organization or PMO for short.

I would make the PMO a true management organization with responsibilities that include but not limited to:

Finally, this PMO concept should be applied appropriately at the state and local levels where their shared status to the federal PMO would result in an even bigger picture.

The PMO concept is only one component to what's needed in reforming the permitting process. The validity of each governing body needs to be evaluated. The steps within each governing body needs to be assessed for validity. Dependencies between the governing bodies need to be defined. And of course buy-in is needed across all these governing bodies -- including at the state and local levels.

As you can see, permit reform is a tall order. However, it is a necessary task. And one that needs to begin ASAP.

Tags